I was born in Egypt to Egyptian parents. As a toddler and preschooler, I spoke the language I heard my parents speak. At school, I learned two languages: Arabic and English. Growing up, I noticed that the Arabic we studied at school was different from the one we spoke in our daily life. When I asked why, the answer was, “What we speak is the Egyptian “dialect” of Arabic.”

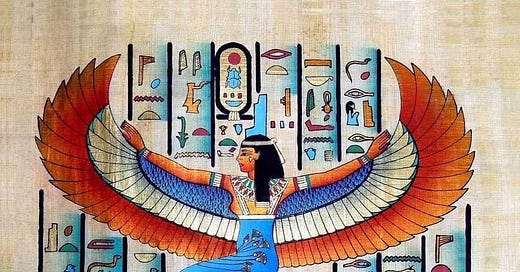

We learned too briefly that the ancient Egyptian language was written in Hieroglyphic. We were never taught how to read the Hieroglyphic script. We were told that the last evolved form of ancient Egyptian was Coptic. Coptic writings were retained in the Egyptian church. “Why don’t we learn Coptic at school?” I wondered. “It’s a dead language; it’s useless,” they said. The church was the only place anyone could learn Coptic in Egypt.

We studied the Arab invasion history in detail and the Arabic language, which has been the official language in Egypt since. “What happened to our Egyptian language?” I asked my teachers. “It died out gradually, and now we speak Arabic,” they replied.

I joined the University and majored in English, and minored in German and French. Linguistics was among my mandatory courses, and it has been a passion of mine since. When I traveled to Germany, France, and the UK, I heard native speakers of the three languages speaking the exact same written languages in books. I questioned, “Why is the linguistic structure of our spoken Arabic completely different from that of classical Arabic?” I never found a convincing answer.

I grew up into adulthood lacking any feeling of belonging and missing all sense of identity. It felt as if my own land was dismissing me altogether. Rebellious against many social traditions in modern Egyptian society, I did not share the same priorities and interests but had different values. I was an outcast.

In my early twenties, I moved continents and settled in Canada. Although English and French have been the official Canadian languages for centuries, Indigenous people still speak their native tongues. That made me wonder why my people could not maintain theirs. It intensified my anger at my ancestors because they let the most essential part of our identity die out.

The orphanhood of having a dead mother tongue, and the homelessness of being a wanderer accompanied me after I left my country. I was indifferent to being Egyptian, neither ashamed nor proud. It was a life fact that I never chose and could never change. Adjusting to the Canadian lifestyle was effortless; language was no barrier. I flourished in Canada on the personal and professional levels and integrated into Canadian society, yet I still felt like an outsider.

I never belonged anywhere, let alone fit in. It was so alienating that sometimes it felt as if I was born on the wrong planet, or perhaps in the mistaken century. When someone showed curiosity and asked about my ethnicity, I escaped answering by asking them to guess. Not a single soul ever guessed it right. I would get Greek, Russian, Mexican, Spanish, Italian, Lebanese, Iranian, anything but Egyptian, as if Egypt had been erased from the map.

Knowing that Arabic was not my native language, I never cared to teach it to my children, who were born in Canada. But when he grew older, my son asked me to teach him Arabic. He learned the alphabet. When he started reading words and sentences, he said to me, “This is not the same language you speak to me at home.” I didn’t know what to tell him. The mystery continued to grow in my life, and through my children’s, with no logical answers.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Further Inquiry to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.